Editing Inertia

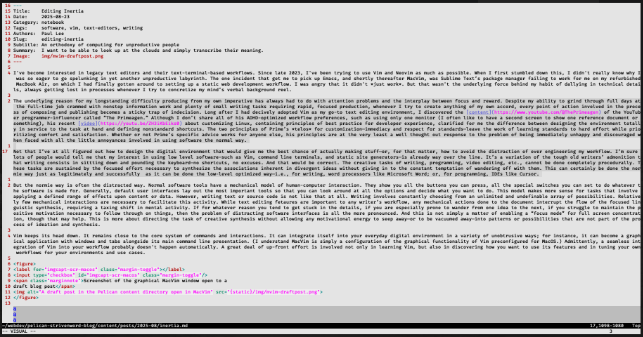

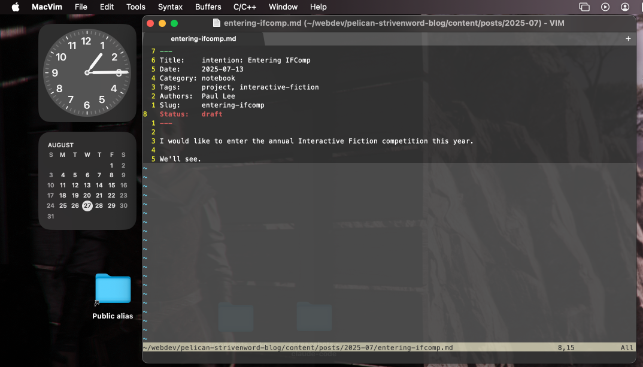

I've become interested in legacy text editors and their text-terminal-based workflows. Since late 2023, I've been trying to use Vim and Neovim as much as possible. When I first stumbled down this rabbit whole into a cavern of twisty little legacy passages, I didn't really know why I was so eager to go spelunking in yet another unproductive labyrinth. The one incident that got me to pick up Emacs, and shortly thereafter MacVim, was Sublime Text’s package manager failing to work for me on my refurbished MacBook Air, on which I had finally gotten around to setting up a static web development workflow. I was angry that it didn't just work. But that wasn’t the underlying force behind my habit of dallying in technical details, always getting lost in processes whenever I try to concretize my mind’s verbal background reel.

The underlying reason for my longstanding difficulty producing from my own imperative has always had to do with attention problems and the interplay between focus and reward. Despite my ability to grind through full days at the full-time job crammed with nonstop information work and plenty of small writing tasks requiring rapid, focused production, whenever I try to create anything of my own accord, every point of action involved in the process of composing and publishing becomes a sticky trap of indecision. Long after I had decisively adopted Vim as my go-to text editing environment, I discovered the content of the YouTuber programmer-influencer called “The Primeagen.” Although I don’t share all of his ADHD-optimized workflow preferences, such as using only one monitor (I often like to have a second screen to show one reference document or something), his recent video about customizing Linux, containing principles of best practice for developer experience, clarified for me the difference between designing the environment totally in service to the task at hand and defining nonstandard shortcuts. The two principles of Prime’s telos for customization—immediacy and respect for standards—leave the work of learning standards to hard effort while prioritizing comfort and satisfaction. Whether or not Prime’s specific advice works for anyone else, his principles are at the very least a well thought out response to the problem of being immediately unhappy and discouraged when faced with all the little annoyances involved in using software the normal way.

Not that I’ve at all figured out how to design the digital environment that would give me the best chance of actually making stuff—or, for that matter, how to avoid the distraction of over engineering my workflow. I’m sure lots of people would tell me that my interest in using low level software—such as Vim, command line terminals, and static site generators—is already way over the line. It’s a variation of the tough old writers’ admonition that writing consists in sitting down and pounding the keyboard—no shortcuts, no excuses. And that would be correct. The creative tasks of writing, programming, video editing, etc., cannot be done completely procedurally. These tasks are sustained by the focused effort necessary to synthesize the associations inherent in divergent ideas without giving in to the constant temptation of wandering off with them. This can certainly be done the normie way just as legitimately and successfully as it can be done the low-level optimized way—i.e., for writing, word processors like Microsoft Word; or, for programming, IDEs like Cursor.

But the normie way is often the distracted way. Normal software tools have a mechanical model of human-computer interaction. They show you all the buttons you can press, all the special switches you can set to do whatever the software is made for. Generally, default user interfaces lay out the most important tools so that you can look around at all the options and decide what you want to do. This model makes more sense for tasks that involve applying a defined range of effects upon content or data. However, writing text or source code is not like that at all. Writing involves constantly choosing from an unlimited and undefinable array of possibilities. Relatively few mechanical interactions are necessary to facilitate this activity. While text editing fetaures are important to any writer’s workflow, any mechanical actions done to the document interrupt the flow of the focused linguistic synthesis, requiring a taxing shift in mental activity. If for whatever reason you tend to get stuck in the details, if you are especially prone to wander from one idea to the next, if you struggle to maintain the positive motivation necessary to follow through on things, then the problem of distracting software interfaces is all the more pronounced. And this is not simply a matter of enabling a “focus mode” for full screen concentration, though that may help. This is more about directing the task of creative synthesis without allowing any motivational energy to seep away—or to be vacuumed away—into patterns or possibilities that are not part of the process of ideation and synthesis.

Vim keeps its head down. It remains close to the core system of commands and interactions. It can integrate itself into your everyday digital environment in a variety of unobtrusive ways; for instance, it can become a graphical application with windows and tabs alongside its main command line presentation. (I understand MacVim is simply a configuration of the graphical functionality of Vim preconfigured for MacOS.) Admittently, a seamless integration of Vim into your workflow probably doesn't happen automatically. A great deal of up-front effort is involved not only in learning Vim, but also in discovering how you want to use its features and in tuning your own workflows for your environments and use cases.

I’m not even a programmer; for me, that is one of the distractions. To be sure, trying to use Vim has lured me down multiple rabbit holes, but I have been persisting, succeeding (I think) in creating a methodology of computing whereby I may be able to write with less mental pain. My interest in command line workflows is piqued not only by the challenge and the hope of better productivity, but also by the continuity, the sense of orthodoxy. I’m hoping to develop a personal digital orthodoxy, a way of working on computers derived out of the evolution of information technology, connected to the standards and syntactic principles that formed the basis of this realization of self-incarnating information. An orthodoxy is a best way forward, as demonstrated by perpetuated information. I’m hoping that respecting the fundamental syntactics of computing will help me attain a more natural, less strained, healthier way forward for my ideas.

When it comes down to it, I want to be able to look up at the clouds and transcribe their meaning into the realm of human semantic representation. I’m betting on my instinctual gravitation toward the old basic elements of computing—the principles still active today’s age of disposable, ubiquitous cloud technology—to help me build practices and structures that will reinforce the foundations of my communities.